|

Butoke’s

Health Activities |

|

|

Butoke

has been striving to construct an integrated health program responding to the

highest priorities. We have been doing this piece by piece, starting with

nutrition, emergency care, and primary care. Our

work builds on that initiated in 2004 by Cécile de Sweemer, who was then

working as a missionary with the Communauté

Presbytérienne au Congo. Drawing upon her own funds and those of benefactors,

Cécile and her associates helped people without means to secure emergency or primary

care through the Good Shepherd Hospital and the Primary Health Care Centre in

Tshikaji. She also took some handicapped people for operations and prostheses

to Jukai. Since

Butoke began operations in Kananga in 2005, we have pursued these actions,

focussing primarily on emergency care and dispensing simple primary care

ourselves. Funding available for these various activities came to about

$US 27,000 in 2004 and $US 10,000 in 2005. Because needs such as

emergency care are acutely felt, these actions are very popular and well

appreciated. |

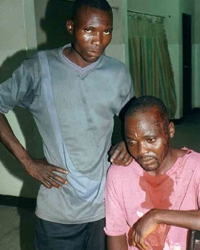

Many emergencies are turned away from hospitals for lack of ability to pay. Butoke provides an advocate who assists hospital patients get access to needed health care. |

|

We are also seeking to develop a coherent

approach, in collaboration with other partners in the region, that takes into

account local problems and opportunities, and helps the most vulnerable

groups to overcome the high levels of morbidity and mortality that they

currently face. Our strategy is based on our analysis of the primary causes

of illness and mortality in the region, with attention to those causes

providing the greatest opportunities for improvement. Most

deaths in Western Kasai are due to malnutrition. WHO once estimated the share

of deaths due to malnutrition at 75%, but the proportion may be even higher

than that. In addition, malnutrition and the reduced level of immunity that

accompanies it are responsible for chronic ill heath due to conditions such

as osteomyelitis, atonic ulcers, and chronic anaemia. For this reason,

Butoke’s principal efforts have been concentrated on food

security and nutrition. |

|

|

The conventional wisdom since the 1960s, based

mostly on Western African and Indian epidemiological studies, is that the big

killers are endemic diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, malaria, and

childhood diseases such as measles. However, the pattern in Western Kasai is

different, in part because these are the diseases upon which local health

services have focused their attention, with a relative degree of success. Our

assessment is that childhood diseases, diarrhoea and pneumonia are not

actually the most important causes of death in Western Kasai. For this reason, and in order best to complement

the work already being carried out by other organizations (for example

UNICEF’s work on basic childhood vaccinations), we are focusing our attention

on the following: ·

Malaria and the extreme anaemia that follows it ·

Meningitis,

typhoid and hepatitis ·

HIV/Aids

and tuberculosis ·

Diabetes ·

Mental

health. |

Health care facilities are sparse. Church hospitals play a major role. |

|

The Global

Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria has popularized the concept

that AIDS, TB, and Malaria are diseases of poverty. This is true. These

diseases hit the poorest the hardest, and are the most difficult for the poor

to combat. The same is true of typhoid and diarrhoea, of hepatitis and

meningitis, and of almost all great killers. In Western Kasai, we are still losing the battle

with malaria, in all layers of society. Most of the deaths that we witness

among people whose care we support are due to malaria and the extreme anaemia

that follows it, especially in small children. To address this problem, we

have prepared a three-year project to combat malaria and the anaemia that

results from it. This project has been submitted to UNDP for funding from the

Global Fund. The proposal emphasizes that the poorest should be given free

access to prevention and free care. Too many people here cannot afford

mosquito nets, or a simple course of treatment. We are hoping for a reply

from UNDP by the end of February. The project covers seven health zones, and

a population of over 900,000. Involvement in this project would provide an

excellent opening for Butoke to launch a societal debate on rights to health

care. |

Butoke

staff provide basic health care. |

|

UNICEF sponsors normal childhood vaccinations,

which are appreciated by most people but coverage is not as thorough as it

should be. It is less than 80%, and, in many areas, less than 60%. The UNDP

malaria program would put us in a position where we can educate people on the

need to take advantage of the UNICEF vaccination program. However, we would

need to go beyond that. Currently the second-level causes of death among

children, adolescents and young adults are meningitis, typhoid and hepatitis.

So far, except for emergency care, we have no systematic response to offer

against these threats. We feel it is becoming imperative we provide

leadership in initiating vaccinations and health education on meningitis,

typhoid and hepatitis. Because typhoid is water borne (as well as food

borne), measures are required to improve access to potable water. The only

practical means of achieving this within a reasonable time would be through

household chlorination. A difficulty in achieving this is that there is fear

of mass poisoning. However, Butoke’s Dr. de Sweemer has had experience

organizing a campaign to chlorinate water supplies in equally poor, low

technology regions of Laos, to combat a cholera epidemic. She has found that

success hinges upon the establishment of a good rapport with the community,

combined with efforts to extinguish suspicions of poisoning. Such efforts

need to be accompanied with basic hygiene education. We have started

exploring whether any of the foundations or the Centre for Disease Control in

Atlanta can help. TB and AIDS, individually or combined, are a

third major cause of death requiring increased attention. We are already in

the process of initiating a program for responsible sexuality, trying to

further prevention of sexually transmitted diseases, as well as better spacing

and planning of births. We are also about to conclude a partnership with

AcsAmocongo (Action contre le SIDA pour un avenir meilleur des orphelins),

which is developing an antiretroviral program in Kananga, with support from

the Global Fund. Our role would be to serve as a referral centre that would

identify people for voluntary testing prior to eventual treatment with

antiretroviral agents. We would also help people to appreciate the importance

of treatment before full-fledged disease breaks out. We would do this in

conjunction with our agricultural activities and thus reach rural populations

that AcsAmocongo could not easily cover. AcsAmocongo has good experience in

Kinshasa but is new to Western Kasai. TB programs exist in each of the major hospitals of

Kananga, but there is a need for complementary support, such as feeding and

transportation, as well as paying for access to the TB program, which is not

entirely free. This is where Butoke has a role to play. We need to expand

these actions to include active screening for TB, and to attack the question

of access to food and simple life support for people suffering from TB.

Research elsewhere (in India) has shown that provision of food for TB

patients did not make any difference, but this was in a context where

afflicted people were not left to starve to death, as is tragically the case

here. We have already helped numerous cases of diabetes

type II and hypertension among people over 40. Most of these people were

overweight, but many others were of almost normal weight but physically

inactive and subsisting on a refined carbohydrate diet, especially

intellectuals, civil servants and traders. We are approaching Help the Aged

Canada to try to see whether they can assist us to provide affordable drugs

in sufficient quantities as well as health education. Diabetes is not yet

nearing epidemic proportions, but in the foreseeable future, if access to

food improves, the disease could spread rapidly unless people change their

dietary habits and the preference of all those who can afford it for physical

inactivity. It would be good to start now educating the younger, still

active, population. We have so far dealt only occasionally with

mental health cases (see story on the tarred woman),

even though many street children and other people around us suffer from

curable mental health cases or are simply social outcasts likely to become

psychotic under the stress. Kananga needs a walk-in program of treatment and

a Salvation-Army-style feeding program for such people. However, Butoke does

not have the human and financial resources to deal with this fully at this

time. Among the most vulnerable populations are

prisoners and the elderly (over 55 years), who suffer all the same problems

as the general population, but in exaggerated forms due to lack of official

or family support. We have launched some first initiatives to support these

people with support of Presbyterian parishes in the US and also Help the Aged

Canada, but they need to be reinforced. Focusing on neglected social groups – whether

they are mentally unstable, prisoners or just elderly – is important not just

for the succour that is provided, but also for the implied message that all

life has intrinsic value and that everyone has certain basic human rights. We

hope that Butoke’s activities in the health sector, like our work in food

security, will provide a measure of hope and resolve to solve problems and

help to preach human rights through concrete actions. |

|